High-profile advances, such as senolytics, have fueled hopes of delaying aging and death, and even immortality. But the reality is more nuanced.

We are born, grow up, reach adulthood, and may have children. Then we get sick, get sick, and eventually die. These are all necessary stages of life—at least for now, although many people wish there were another way.

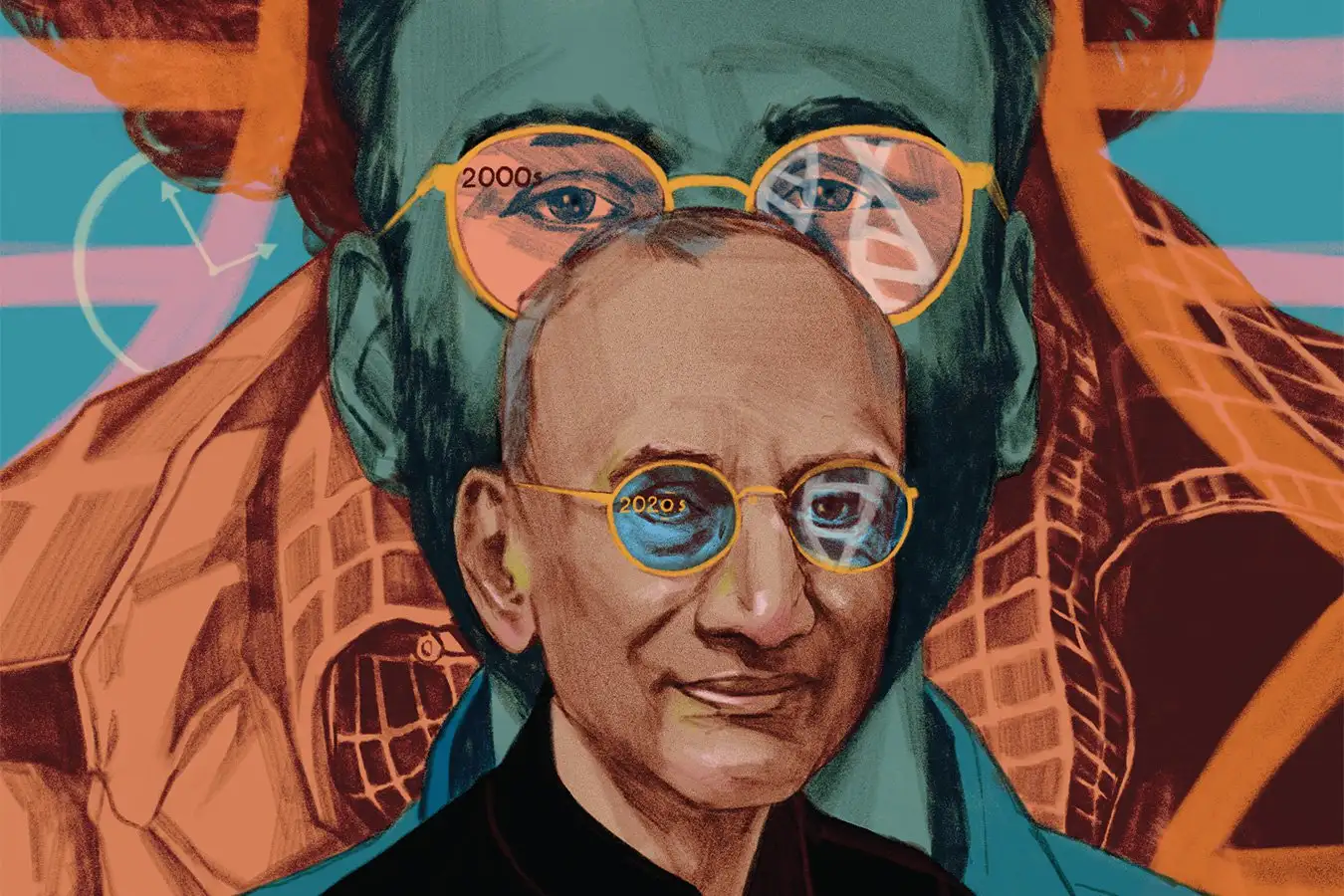

Maybe there is. Some have suggested that advances in aging research have led us to believe that aging and death can be delayed—even by hundreds of years. Is this wishful thinking? In his timely and illuminating new book, Why We Die, Venki Ramakrishnan, winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, explains the science and helps us separate fact from fiction.

Over the past 100 years or so, improved hygiene, better living conditions, and innovative medical treatments, such as antibiotics and vaccines, have more than doubled the human lifespan. But the maximum lifespan has been set at 120, and it’s hard to top it. At the end of a long life, many people are now dealing with aging for longer.

Stopping Time

The idea of stopping aging and death has been the subject of speculation, belief, and myth since ancient times. The pyramids of ancient Egypt were built by people who believed that the pharaohs could be reborn, and the search for the “Fountain of Youth” is a perennial topic in human stories. Modern science has shown us what problems this search will encounter. Aging occurs naturally when an organism passes the stage where it can pass on its genes to the next generation. After that, there is no selective pressure to stop the process of degeneration and decline.

Research has found many biological hallmarks of aging: DNA accumulates damage, chromosome ends shorten, proteins clump, organelles such as mitochondria malfunction, stem cell numbers decrease, and organs become chronically inflamed. These problems mainly reflect increased molecular chemical damage that affects all cellular systems, including the maintenance, repair, and regeneration processes that would otherwise offset such degeneration. This sets in motion a vicious cycle that ultimately triggers cellular aging and death, bringing the organism to its inevitable end.

Ramakrishnan explains these basic processes of aging in a way that is easy to understand (some of the complex concepts do require repeated reading for those who are new to the subject). Now, a fundamental question facing researchers is: How are these various aspects of aging connected? Is aging caused by a single factor or multiple factors? Which factors are more important? Although scientists still debate, a large body of evidence supports the view that the ultimate cause is the accumulation of DNA damage—through oxygen free radicals, ultraviolet and X-ray radiation, smoking, blood therapy, alcohol, many natural metabolites, and even mediators such as water. This understanding is key to obtaining reliable biomarkers of aging from tissues or blood. Someone has already accomplished this feat through the clever discovery of epigenetic clocks in our genomes. However, this information is more important for revealing targets that can intervene in the aging process.

The Mystery of Longevity

Advances in anti-aging methods, such as the discovery of compounds called “senolytics” that can clear out senescent cells, have attracted a lot of public attention and commercial interest. But even scientists find it difficult to declare that a research result is reliable or inaccurate, promising or only preliminary.

Although not a professional aging researcher, Ramakrishnan provides a lot of insights in this book. He conducted in-depth research: critically reading the literature, consulting leading experts, and most importantly, using independent thinking and common sense. His interviews with researchers in the field gave him a peek behind the

scenes and interesting information that could not be found in textbooks or academic journals. The book is full of anecdotes, unique characters, and valuable historical perspectives, making it more than a simple summary of cutting-edge research.

scenes and interesting information that could not be found in textbooks or academic journals. The book is full of anecdotes, unique characters, and valuable historical perspectives, making it more than a simple summary of cutting-edge research.

So what is hot and what is not? Dietary restriction has long been recognized as a way to slow aging and extend life, but Ramakrishnan pointed out that this practice is not popular. He then discussed how people have been looking for drugs that can mimic this effect, with some success. Inhibiting mTOR, a key enzyme found in many organisms, can modestly extend the lifespan of organisms, but its efficacy in humans seems to be limited. Although the authors do not mention it, GLP-1 receptor agonists, approved drugs that treat diabetes and obesity by reducing appetite and weight, may be a good alternative.

The use of senolytics has raised people’s expectations because they can bring multiple benefits to mice. But cellular senescence takes more than one form and is critical for development, stress response, and cancer prevention, complicating its use in humans. Such concerns also arise from strategies that deliver factors from the blood of young donors to old recipients, which have been shown to rejuvenate old mice to some extent. However, studies have shown promising results in reprogramming adult mouse cells into stem-like cells by briefly expressing specific transcription factors that control early developmental genes. Such techniques could one day be used in humans if safety issues can be addressed.

A lifetime of health

However, strategies to replace cells for regeneration do not work for all tissue types. Such approaches are particularly inappropriate for the brain, where most neurons must be alive and functioning throughout our lives. Although methods have been developed to grow clusters of differentiated neurons called mini-brains, this still poses a major obstacle. The name “mini-brains” is actually too optimistic, because these mini-brains are not as complex and comprehensive as real brains. Even more unrealistic is the idea that some people support: that a person’s brain or even the whole body can be preserved by storing it in liquid nitrogen until new technology is available to revive it later. These people believe in such methods to a degree that is a bit like the Egyptians’ belief that their pharaohs can be resurrected.

Discover more from Personal Blog of Richard Tong

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.